High Blood Pressure after Eating: Signs, Causes, Foods to Eat & Avoid

Key Takeaways:

- High blood pressure after eating is not typical. Gastrointestinal blood flow (blood flow to your guts) is higher when your body digests the food. So, BP usually drops following a meal, especially in older adults.

- Salty, sugary, high-fat processed foods can raise blood pressure quickly.

- To measure your BP, wait at least 30 minutes after eating to have accurate readings.

- If you have high BP (e.g., 130–139 to 80–89 mm Hg) even 1 hour after eating, consult a healthcare professional.

- High blood pressure medications, e.g., Enalapril, and a healthy lifestyle, can help you achieve the ideal level.

Blood pressure can increase after eating, but most people are not aware that they have this problem. Because, high BP or hypertension often does not come with any warning signs.

If left untreated, it raises the risk of heart attack or stroke. The World Health Organization (WHO) calls this condition the “silent killer”. Unfortunately, 46% of people with high BP do not know they have it.

So, it’s important to know when your blood pressure is going lower or higher.

In this article, we will explore whether high blood pressure following a meal is normal and look at certain foods that can raise blood pressure quickly. This will help you prevent high BP from weakening your heart or affecting other organs.

Table of Contents

Blood Pressure Levels – What Is Normal?

Normal systolic blood pressure (the top number) is less than 120 mm Hg, and normal diastolic blood pressure (the bottom number) is lower than 80 mm Hg. So, 120/80 indicates healthy normal limits.

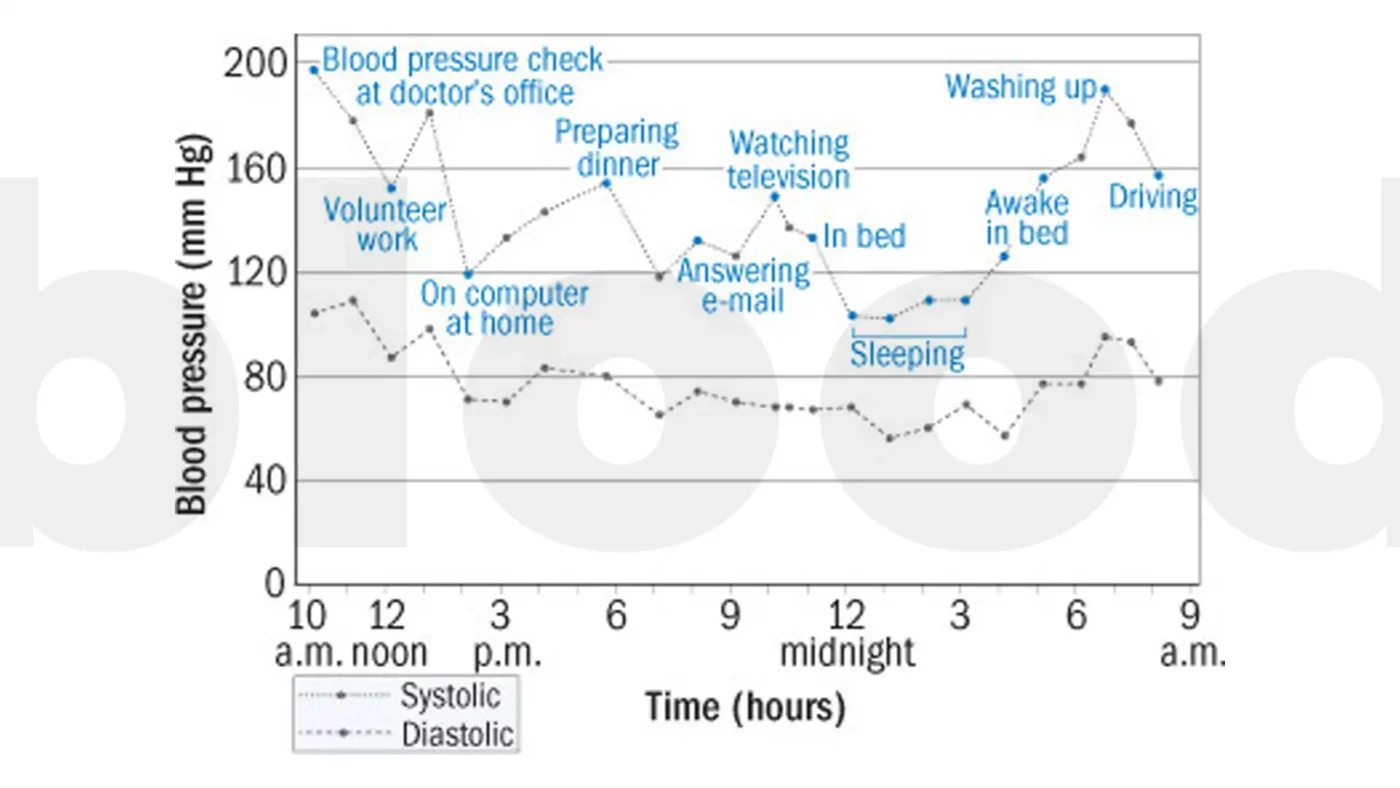

Your BP rises and falls many times throughout the day. Most of the time, this is not a reason to be concerned.

Blood pressure fluctuations. Source: Harvard Health Publishing

However, “blood pressure regulation,” or systemic arterial pressure, is carried out by the body so sufficient blood can reach tissue and organs.

If you have high BP, blood pressure is ongoing, pushing against the walls of your arteries (blood vessels). This burdens the heart, which has to work extra hard to pump blood.

According to the U.S. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), here’s when BP readings fall outside the normal range.

- Elevated blood pressure

A systolic pressure is 120 – 129 mm Hg, and a diastolic pressure is less than 80 mm Hg.

- Stage 1 hypertension

A systolic pressure is 130 – 139 mm Hg, and a diastolic pressure is between 80 and 89 mm Hg. It’s also called prehypertension, which means you’re at a great risk of high BP. It’s sort of a “warning sign”.

- Stage 2 hypertension

A systolic pressure of 140 mm Hg or higher. Or a diastolic pressure of 90 mm Hg or higher

If your BP reading is higher than 180/120, it’s a hypertensive crisis and needs immediate medical attention. The symptoms of hypertension may include headaches, chest discomfort, shortness of breath, and nosebleeds.

Some people may have dangerously high BP without any signs and symptoms.

Is It Normal to Have High Blood Pressure after Eating?

Some people feel dizzy after a heavy meal. This doesn’t happen due to high bp; the reason is exactly the opposite.

After eating, gastrointestinal blood flow normally increases to digest the food. The heart rate goes up to maintain normal pressure in the rest of the body. The blood vessels in other areas constrict (become narrow), making less space for blood to flow.

In some elderly patients, this mechanism doesn’t work as it should. As a result, the blood pressure dips sharply in the rest of the body, making them feel dizzy and lightheaded.

This is a common phenomenon known as postprandial hypotension (PPH). “Postprandial” means “after you have a meal”.

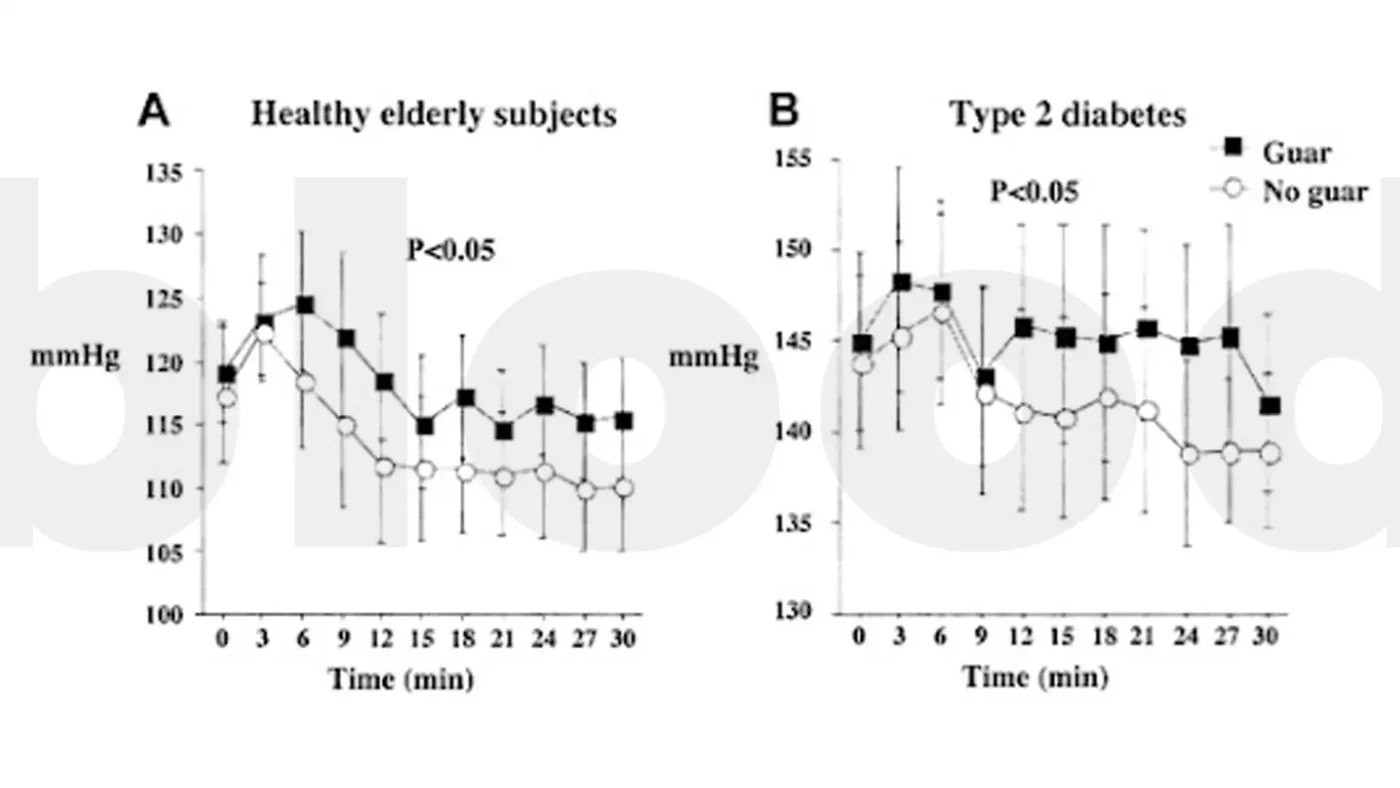

Source: “Postprandial Hypotension: A Systematic Review” Journal of the American Medical Directors Association

Studies reveal that about 40% of people aged above 65 have PPH. This may also happen if you have an underlying health problem, e.g., diabetes.

Even healthy adults can experience a temporary slight dip in blood pressure after eating. In a study, postprandial BP increased in subjects quickly after they had a standard breakfast (with toast, margarine, and jam) and water. Then, both systolic and diastolic BP fell within 45 minutes, after which it started returning to normal.

So, typically, it is not normal to experience high BP after eating. But when you do, it may be due to certain foods.

Can Some Foods Raise Blood Pressure Immediately?

Your eating habits can affect your blood pressure in several ways. If you’re dealing with high BP or have a higher-than-average risk, you may need to cut down on certain foods that can worsen your condition.

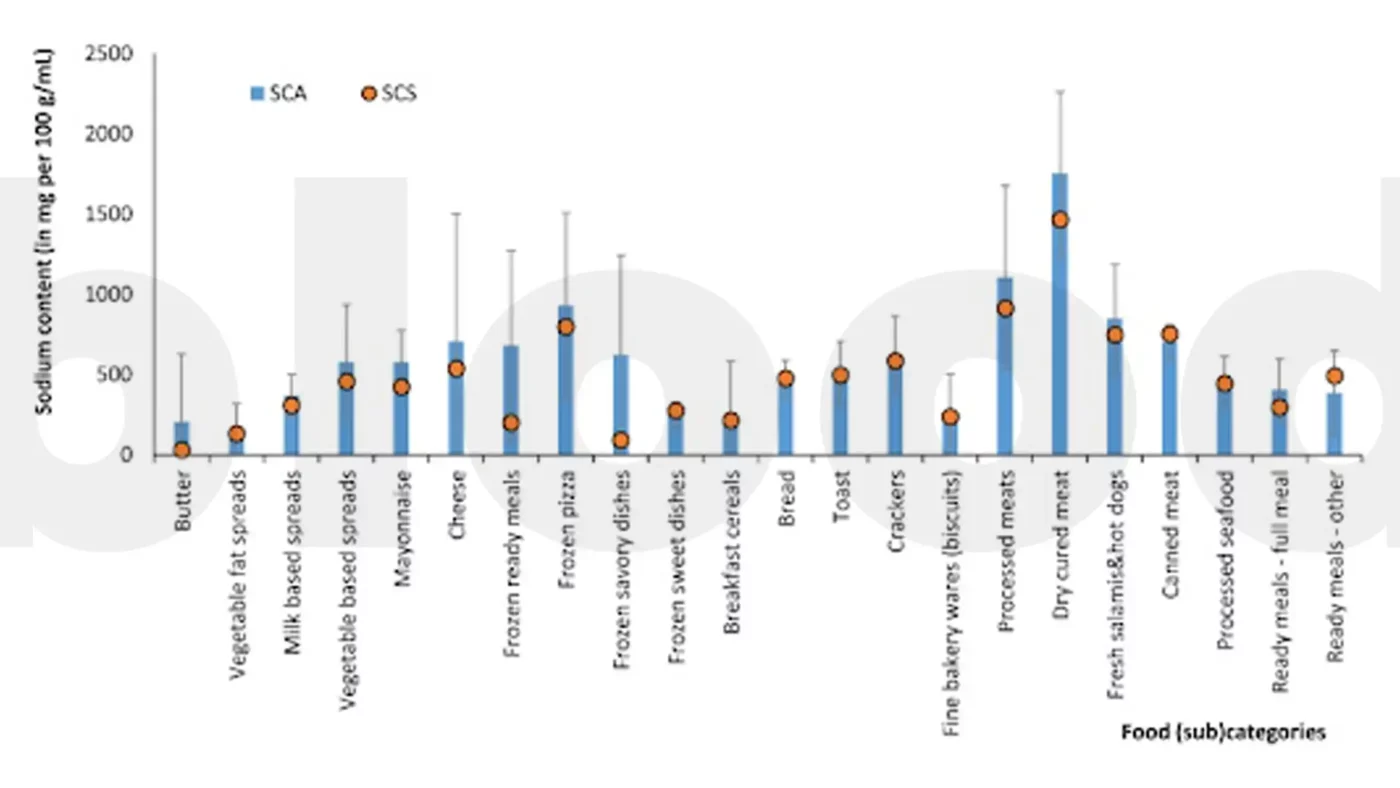

Salty foods

High salt intake leads to fluid retention in your body. This increases the volume of blood, raising its pressure against the walls of the arteries.

According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food Data Central, a 14-inch pizza contains 5,100 mg of sodium, almost twice the daily recommended intake.

Processed meats and red meats

Besides cancer risks, processed meats, such as ham, hot dogs, and sausage, are too high in sodium. Even non-processed red meat, such as beef or pork, can cause high blood pressure and increase cardiovascular risks.

Sugary foods and beverages

Foods high in sugar are omnipresent, e.g., candies, desserts, soda, cola, and hundreds of packaged beverages. The insulin spike after consuming sugar can damage blood vessels and increase blood pressure.

Foods with saturated fats and trans fat

Some foods can increase LDL (low-density lipoprotein) cholesterol and triglycerides, which may raise blood pressure. Examples are baked foods, fries, ice cream, and even some cereal bars and snacks that are sold as “healthy.”

They may thicken blood vessels, resisting blood flow. This is referred to as the “hardening of the arteries” due to plaque buildup, such as fat, cholesterol, and other substances.

Cookies, pastries, pies, and baked goods high in saturated fats are also risk factors for high blood pressure and cardiovascular problems.

Frozen meals, pre-packed or processed foods

Ready-to-eat meals and frozen dinners can contain excess sodium. We have evidence of a strong link between ultra-processed foods (UPF) and arterial hypertension.

In a study, people who consumed a lot of UPF had a 23% higher risk of hypertension.

So, if you’re wondering, “Why does my blood pressure go up immediately after eating?” it may be a good idea to skip the processed or ready-to-eat foods on your next grocery trip.

So, how much does blood pressure rise after eating those foods? It depends. Just one soft drink can increase your BP by 2.08 m Hg.

On the other hand, healthy food sources (e.g., DASH or Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) can help manage blood pressure.

| Category | Worst Foods for High BP | Best Foods for High BP |

|---|---|---|

| High-Sodium Foods | Table salt, sauces, pickles, instant savory foods, pizza, fast foods, processed meats (ham, bacon, sausage) | Potassium-rich fruits (bananas, oranges), dried fruits, spinach, other leafy greens |

| Saturated and Trans Fats | Cheese, creamer, butter, margarine, fries, crisps, baked foods | DASH diet: whole grains (e.g., oatmeal, brown rice), lean proteins (chicken, fish), nuts, seeds, low-fat/fat-free dairy |

| Sugary Foods | Sugary beverages (soda, cola, tea, coffee with added sugar), candies, sweetened breakfast cereals | Healthy snacks: cottage cheese, hummus, hard-boiled eggs, yogurt, edamame, nuts, and seeds |

| Alcohol | Excessive alcohol consumption | Moderate or limited alcohol intake; adequate hydration with water |

Can Not Eating Cause High Blood Pressure?

Not eating or irregular meal timing may seem to be harmless, but they affect your BP levels.

- A study shows that women who skipped breakfast had higher cortisol (stress-hormone) levels, which may lead to hypertension.

- Not drinking water for a long time can cause the blood vessels to tighten (constrict), increasing blood pressure (BP).

- Fasting every alternate day may impact the activities of insulin (a sugar-regulating hormone). According to the American Heart Association, hypertension and insulin resistance are correlated.

- Skipping meals or crash diets (reducing calorie intake severely) can trigger urges to overeat and binge-eat later. This can lead to a large increase in BP.

However, planned intermittent fasting (IF) can provide some benefits.

- Fasting followed by a DASH diet can trigger changes in the microbiome, the balance of bacteria in the gut. This helps lower BP.

- A study published in the European Journal of Preventive Cardiology shows that one-day intermittent fasting can be useful for obese people with hypertension.

However, we still need more data to confirm the beneficial effect and safety of fasting on BP.

I Eat a Healthy Diet. Why Do I Still Have High Blood Pressure?

Your dietary habits aren’t the only cause or risk factor behind high BP. Let’s say you eat nutrient-dense foods and have regular meals. Does your blood pressure still go up after you eat?

It may be due to some underlying medical conditions such as:

- Obstructive sleep apnea, a sleep disorder

- Diabetes

- Metabolic syndrome

- Renal hypertension

- Polycystic kidney disease

- Thyroid dysfunctions

- Adrenal gland disorders

- Pheochromocytoma, a tumor in the adrenal gland usually benign

- Cushing’s disease (too much production of the stress hormone cortisol)

- Lupus (Systemic Lupus Erythematosus), an autoimmune disease

- Liddle syndrome (a rare, inherited kind of high BP)

Check with your doctor to rule out the possibility of a serious health problem.

Other factors that may affect your blood pressure are:

- Age: Older adults are prone to high BP because their arteries tend to stiffen, causing isolated systolic hypertension

- Smoking, drinking alcohol, and substance use

- Gender: Women are prone to have a high BP after menopause.

- Obesity: Being overweight is the reason for 65–78% of cases of hypertension.

- Race: Black adults are more likely to have hypertension.

- Pregnancy: Gestational hypertension develops during pregnancy.

- Genetics

- Sedentary lifestyle, not having enough physical activity

- Certain medications, e.g., pain medications, decongestants, antidepressants like SSRIs, and some birth control pills, can cause your BP to rise.

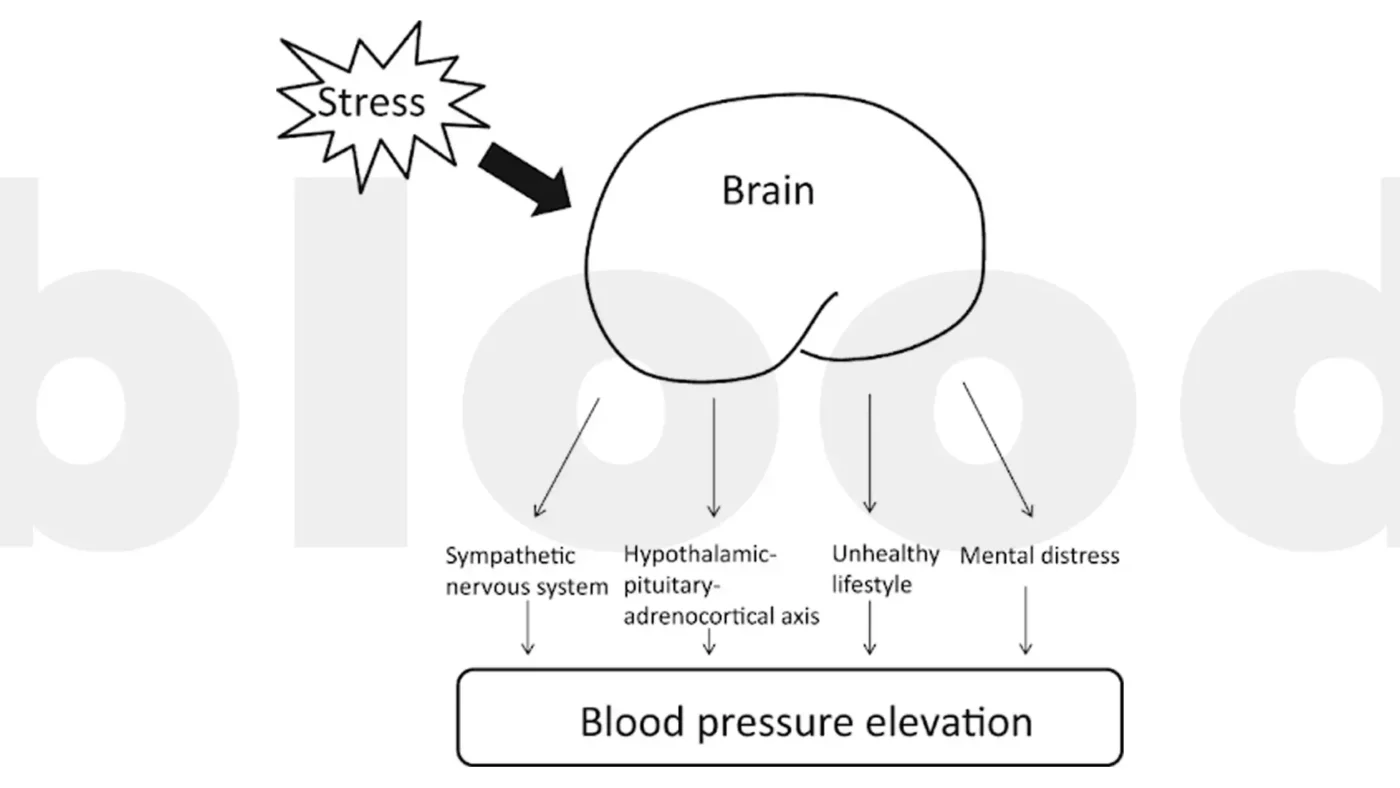

When we’re stressed, our body releases stress hormones like cortisol and adrenaline. While stress itself isn’t a direct cause, repeated bouts of stress and anxiety can elevate your blood pressure levels over time.

Does your blood pressure seem to be higher in a clinic or hospital than in a home setting? It’s called “white-coat hypertension.” Health checkups can make people a bit worried and stressed. So, seeing healthcare professionals (wearing white coats) examine how you’re doing may elevate your BP!

When Should You Check Blood Pressure?

Different activities influence blood pressure, causing it to fluctuate throughout the day. Check it every day around the same time. Ideally, to monitor your BP level, measure it twice daily, once in the morning and once in the evening.

- Do not check blood pressure after eating, smoking, or drinking. Wait for at least 30 minutes.

- Wait for 30-45 minutes after exercising.

- Empty your bladder before measuring the levels.

- Sit and relax by sitting with a straight back, uncrossed legs, and both feet touching the floor.

- Rest the arm on a flat surface before taking the reading after 5 minutes in this position.

- Measure thrice at one-minute intervals to take an average value.

- Do not talk or move your arm during the measurement, which may affect the final result.

Other things to take care of:

- Make sure the room temperature is normal for you. Your BP may spike temporarily if you feel cold.

- Use the correct cuff size. If the cuff is too tight or loose, your blood pressure levels can be affected.

- Put the cuff on bare skin. Putting it over clothing can affect the findings.

- Relax your mind and avoid stressful thoughts.

Each time you check your BP, take two readings, with a gap of at least one minute between them.

When to Consult a Doctor?

Home blood pressure monitoring should not replace in-person visits to your healthcare provider.

According to MedlinePlus, National Library of Medicine (NLM), every person aged three or above should have their BP checked at least every 12 months.

This is advisable if you’re in a high-risk group, e.g., already have a family history of heart conditions, high BP or diabetes, have poor eating habits (high-sodium, low-potassium diet), have an unhealthy lifestyle, are obese, or are aging.

If your systolic BP is 120–139 or your diastolic pressure, 80–89, you have prehypertension. It’s beyond optimal or normal level, but it’s not a cause of concern yet. If it’s higher, there are greater chances of long-term complications. In either case, speak to your doctor straight away.

Your doctor will evaluate your overall health and determine the root cause of high BP. You’ll likely be advised to take ‘anti-hypertensive’ oral medications like Enapril. They would recommend an appropriate treatment plan and lifestyle changes to control high blood pressure.

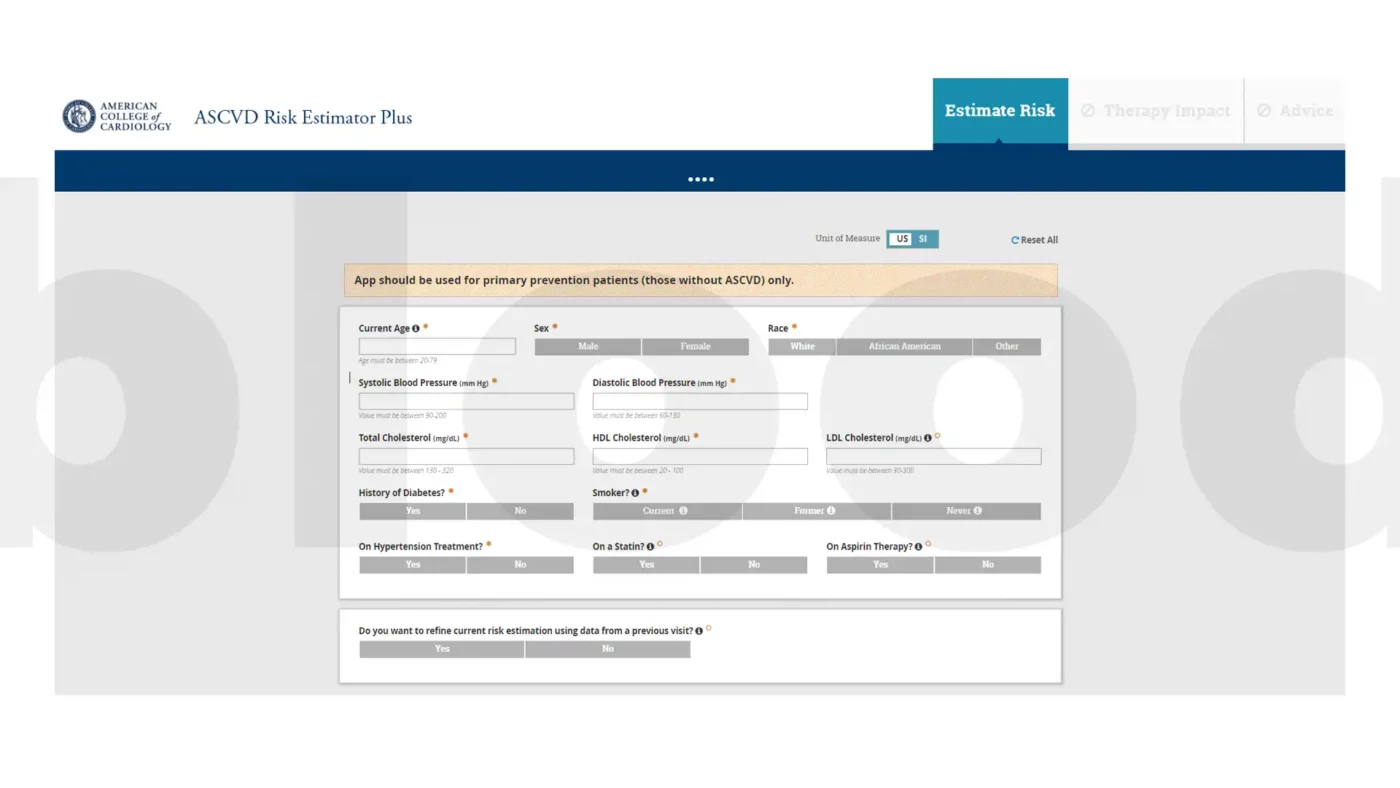

The American College of Cardiology provides a peer-reviewed online free calculator to assess your risk of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD).

Source: ASCVD Risk Estimator Plus, American College of Cardiology

ASCVD, or cholesterol plaque buildup in arterial walls, is the reason behind half of all deaths in Western societies.

Keeping your blood vessels healthy by managing your BP is the best way to avoid this problem.

Final Thoughts

Whether your blood pressure will be higher after eating or not depends on what you eat. To control your BP, cut down on processed junk food, such as those high in salt, sugar, and fat.

Many other factors, like drinking alcohol, smoking, exercising, etc., may influence the blood pressure results. Temporary spikes are normal and nothing to worry about. If your BP increases immediately after eating and doesn’t go back to the pre-meal level even after an hour, and it keeps happening repeatedly, visit your physician.

FAQs

References

- World Health Organization: WHO & World Health Organization: WHO. (2023, March 16). Hypertension. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hypertension

- Harvard Health. (2009, August 1). Experts call for home blood pressure monitoring. https://www.health.harvard.edu/heart-health/experts-call-for-home-blood-pressure-monitoring

- Shahoud, J. S., Sanvictores, T., & Aeddula, N. R. (2023, August 28). Physiology, arterial pressure regulation. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538509/

- What is high blood pressure? | NHLBI, NIH. (2024, April 25). NHLBI, NIH. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/high-blood-pressure

- Severe asymptomatic hypertension: evaluation and treatment. (2017, April 15). PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28409616/

- Kvietys, P. R. (2010). Postprandial hyperemia. The Gastrointestinal Circulation – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK53094/

- Trahair, L. G., Horowitz, M., & Jones, K. L. (2014). Postprandial Hypotension: A Systematic Review. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 15(6), 394–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2014.01.011

- Huang, L., Li, S., Xie, X., Huang, X., Xiao, L. D., Zou, Y., Jiang, W., & Zhang, F. (2024). Prevalence of postprandial hypotension in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age And Ageing, 53(2). https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afae022

- Ahuja, K. D., Robertson, I. K., & Ball, M. J. (2009). Acute effects of food on postprandial blood pressure and measures of arterial stiffness in healthy humans. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 90(2), 298–303. https://doi.org/10.3945/ajcn.2009.27771

- Farquhar, W. B., Edwards, D. G., Jurkovitz, C. T., & Weintraub, W. S. (2015). Dietary sodium and health. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 65(10), 1042–1050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2014.12.039

- Farquhar, W. B., Edwards, D. G., Jurkovitz, C. T., & Weintraub, W. S. (2015b). Dietary sodium and health. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 65(10), 1042–1050. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2014.12.039

- FoodData Central. (n.d.). https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/fdc-app.html#/food-details/173292/nutrients

- Sparks, E., Farrand, C., Santos, J. A., McKenzie, B., Trieu, K., Reimers, J., Davidson, C., Johnson, C., & Webster, J. (2018). Sodium Levels of Processed Meat in Australia: Supermarket Survey Data from 2010 to 2017. Nutrients, 10(11), 1686. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10111686

- Allen, T. S., Bhatia, H. S., Wood, A. C., Momin, S. R., & Allison, M. A. (2022). State-of-the-Art Review: Evidence on red meat consumption and Hypertension Outcomes. American Journal of Hypertension, 35(8), 679–687. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/hpac064

- Salvetti, A., Brogi, G., Di Legge, V., & Bernini, G. (1993). The Inter-Relationship between Insulin Resistance and Hypertension. Drugs, 46(Supplement 2), 149–159. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-199300462-00024

- Korošec, Ž., & Pravst, I. (2014). Assessing the Average Sodium Content of Prepacked Foods with Nutrition Declarations: The Importance of Sales Data. Nutrients, 6(9), 3501–3515. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu6093501

- De Oliveira Da Silva Scaranni, P., De Oliveira Cardoso, L., Chor, D., Melo, E. C. P., Matos, S. M. A., Giatti, L., Barreto, S. M., & De Jesus Mendes Da Fonseca, M. (2021). Ultra-processed foods, changes in blood pressure and incidence of hypertension: the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil). Public Health Nutrition, 24(11), 3352–3360. https://doi.org/10.1017/s136898002100094x

- Hernández-López, R., Canto-Osorio, F., Vidaña-Pérez, D., Torres-Ibarra, L., Rivera-Paredez, B., Gallegos-Carrillo, K., Velazquez, R., Ramírez, P., Barrientos-Gutiérrez, T., Salmerón, J., & López-Olmedo, N. (2022). Soft drink and non-caloric soft drink intake and their association with blood pressure: the Health Workers Cohort Study. Nutrition Journal, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-022-00792-y

- DASH Eating Plan | NHLBI, NIH. (2001, January 4). NHLBI, NIH. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/education/dash-eating-plan

- Witbracht, M., Keim, N. L., Forester, S., Widaman, A., & Laugero, K. (2015). Female breakfast skippers display a disrupted cortisol rhythm and elevated blood pressure. Physiology & Behavior, 140, 215–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2014.12.044

- Quesada, O., Claggett, B., Rodriguez, F., Cai, J., Moncrieft, A. E., Garcia, K., Del Rios Rivera, M., Hanna, D. B., Daviglus, M. L., Talavera, G. A., Merz, C. N. B., Solomon, S. D., Cheng, S., & Bello, N. A. (2021). Associations of insulin resistance with systolic and diastolic blood pressure: a study from the HCHS/SOL. Hypertension, 78(3), 716–725. https://doi.org/10.1161/hypertensionaha.120.16905

- Mechanisms that link compulsive binge eating with hypertension identified. (2015, March 15). ScienceDaily. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2015/03/150330141356.htm

- Maifeld, A., Bartolomaeus, H., Löber, U., Avery, E. G., Steckhan, N., Markó, L., Wilck, N., Hamad, I., Šušnjar, U., Mähler, A., Hohmann, C., Chen, C., Cramer, H., Dobos, G., Lesker, T. R., Strowig, T., Dechend, R., Bzdok, D., Kleinewietfeld, M., . . . Forslund, S. K. (2021). Fasting alters the gut microbiome reducing blood pressure and body weight in metabolic syndrome patients. Nature Communications, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-22097-0

- Isayeva, A., & Matiashova, L. (2022). Effect of one-day intermittent fasting on 24-hour blood pressure profile in hypertensive and normotensive patients with overweight and obesity. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 29(Supplement_1). https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjpc/zwac056.116

- Naha, S., Gardner, M. J., Khangura, D., Kurukulasuriya, L. R., & Sowers, J. R. (2021, August 7). Hypertension in diabetes. Endotext – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279027/

- Stanciu, S., Rusu, E., Miricescu, D., Radu, A. C., Axinia, B., Vrabie, A. M., Ionescu, R., Jinga, M., & Sirbu, C. A. (2023). Links between Metabolic Syndrome and Hypertension: The Relationship with the Current Antidiabetic Drugs. Metabolites, 13(1), 87. https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo13010087

- Berta, E., Lengyel, I., Halmi, S., Zrínyi, M., Erdei, A., Harangi, M., Páll, D., Nagy, E. V., & Bodor, M. (2019). Hypertension in thyroid disorders. Frontiers in Endocrinology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2019.00482

- Chemaitilly, W., Wilson, R. C., & New, M. I. (2003). Hypertension and adrenal disorders. Current Hypertension Reports, 5(6), 498–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-003-0058-1

- High blood pressure and older adults. (2022, October 1). National Institute on Aging. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/high-blood-pressure/high-blood-pressure-and-older-adults

- Yadav, J., Allarakha, S., Shekhar, C., & Jena, G. P. (2021). Alcohol and tobacco influencing prevalence of hypertension among 15–54 years old Indian men: An application of discriminant analysis using National Family Health Survey (NFHS), 2015–16. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, 12, 100894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cegh.2021.100894

- High blood pressure and older adults. (2022b, October 1). National Institute on Aging. https://www.nia.nih.gov/health/high-blood-pressure/high-blood-pressure-and-older-adults

- Shariq, O. A., & McKenzie, T. J. (2020). Obesity-related hypertension: a review of pathophysiology, management, and the role of metabolic surgery. Gland Surgery, 9(1), 80–93. https://doi.org/10.21037/gs.2019.12.03

- Ogunniyi, M. O., Commodore-Mensah, Y., & Ferdinand, K. C. (2021). Race, ethnicity, hypertension, and heart disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 78(24), 2460–2470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2021.06.017

- Calvi, A., Fischetti, I., Verzicco, I., Murri, M. B., Zanetidou, S., Volpi, R., Coghi, P., Tedeschi, S., Amore, M., & Cabassi, A. (2021). Antidepressant drugs effects on blood pressure. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2021.704281

- Munakata, M. (2018). Clinical significance of stress-related increase in blood pressure: current evidence in office and out-of-office settings. Hypertension Research, 41(8), 553–569. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-018-0053-1

- Measuring blood pressure. (n.d.). https://medlineplus.gov/lab-tests/measuring-blood-pressure/#:~:text=A%20blood%20pressure%20measurement%20is%20often%20included%20as%20part%20of,may%20need%20testing%20more%20often

- Enapril (Enalapril) tablet for high blood pressure. (2021, August 16). Hisblue. https://hb.wushymommy.com/product/enapril-tablet

- Treatment | NHLBI, NIH. (2024, April 30). NHLBI, NIH. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/high-blood-pressure/treatment

- ASCVD Risk Estimator +. (n.d.). https://tools.acc.org/ASCVD-Risk-Estimator-Plus/#!/calculate/estimate/

- Pahwa, R., & Jialal, I. (2023, August 8). Atherosclerosis. StatPearls – NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507799/

- Measure your blood pressure. (2024, May 15). https://www.cdc.gov/high-blood-pressure/measure/index.html

- Hansen, R. M., Krogh, K., Sundby, J., Krassioukov, A., & Hagen, E. M. (2021). Postprandial hypotension and spinal cord injury. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(7), 1417. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10071417

Disclaimer

HisBlue is not a substitute for professional medical care or advice from your doctor. The health information on the HisBlue website is general and provided for your information only. We have ensured our content is accurate and current, with reviews by expert doctors. However, we cannot guarantee its accuracy or timeliness. This information is not meant to replace the diagnosis, treatment, or judgement of your doctor or another qualified healthcare provider.